Stephen Curry walked to the bench lugging a superstar’s dilemma: He had played poorly, but his team was going to win. Seventy-nine seconds remained in Game 5 of an NBA Finals that had been framed—to an illogical degree, in Curry’s mind—as a referendum on Curry’s career. If he was truly one of the best players of all time, why hadn’t he won a Finals MVP award? Curry is driven by winning and by lifting others—motivations that are fraternal, not identical, twins. The Warriors would win this game, but he had not lifted them. Curry sat down next to coach Steve Kerr, at the intersection of pride and selflessness. He seemed, Kerr says, “pensive more than anything.”

As much as ever, Curry was in the spotlight, and yet still people did not really see him. If he thinks about his place in history, he never says it, and he found the Finals MVP conversation annoying: “It bothered me that I had to answer to it. It didn’t bother me that it wasn’t on my résumé yet.” The idea that he is lacking something is foreign to him. The implication that he needed to prove himself on the biggest stage was silly.

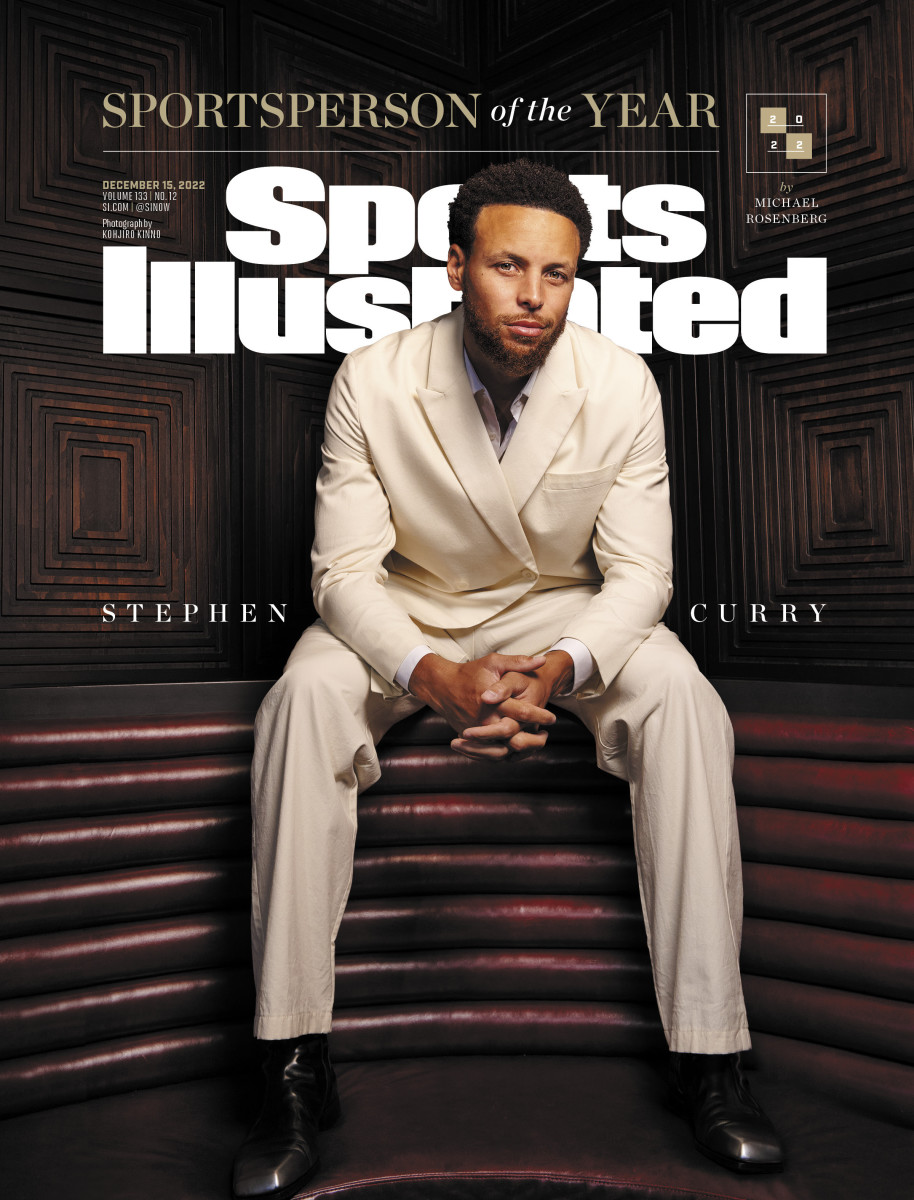

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Get SI’s Sportsperson of the Year Issue

Curry is a boisterously ostentatious performer, and confidence is his oxygen. He once missed his first nine three-point attempts in a playoff game and when he sank the 10th he shimmied. As the Celtics finished off Game 3 to take a 2–1 series lead, Curry told them to their faces to enjoy their last win. Then he told his childhood friend, Omar Carter, he wanted to celebrate in Boston—meaning the Warriors would win three straight and wrap up the title in Game 6. Now they had won Game 4 and were about to take Game 5 in San Francisco.

Kerr turned to his star.

“This is like the best thing that possibly could have happened,” Kerr said.

“What do you mean?” Curry asked.

“We just won this game going away when you had a tough night,” Kerr said. “Do you know how that makes Boston feel?”

Curry thought about it, agreed his coach was right and made the kind of small recalibration that comes so easily to him. Before this year, Curry had not won a playoff game since 2019. His Splash Brother, Klay Thompson, had missed two and a half seasons because of injuries. Curry turned 34 in March. After Game 5, in his suite under the Chase Center, Curry received another reminder of time passing: His college coach, Bob McKillop, informed him he was retiring.

Curry came out in Game 6 and made the Celtics feel even worse: 34 points on 21 shots, seven rebounds, seven assists, two steals, one block and one more championship. It required an indomitability even beyond what he showed in winning two MVPs and his first three championships. He calls it his “greatest moment,” and even this modest brag is so unlike Curry that his wife, Ayesha, says, “Really—he said that?” At the Warriors’ afterparty, in a club underneath TD Garden, Ayesha said, “I’m so proud of you! You did it!” Steph corrected her: “We did it.”

After missing the Warriors’ final 12 games, Curry showed no ill effects in leading his team past Boston.

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

Curry knew people had said the Warriors were finished. He says, “I’m an internalizer. I internalized that throughout the entire year, the last three years. … Just let it marinate.” In the euphoria after Game 6, he uttered one of the most viral sports comments of the year:

“What are they gonna say now?”

It was interpreted as Curry shutting up the doubters. He was also dismissing the nitpicky nature of the whole Finals MVP criticism. Curry admits, “I definitely log receipts,” as most greats do, but he does it only because the receipts are useful. As a lightly recruited kid and overlooked young NBA player, he was easily motivated. After he became a widely praised superstar, he had to manufacture reasons to bust his ass in January and July, even though he knew it was just a motivational game he was playing with himself.

“It’s like a hybrid car,” Curry says. “Once the juice runs out, you gotta go to the reserve tank a little bit.”

He says the ensuing discussion about slaying his haters was “almost a little awkward.” The story of the Finals became about how critics had affected Steph Curry. But the story of his life is how he affects everybody else.

This is What Steph Curry did this year: He won his fourth championship. He won that Finals MVP award after scoring an efficient 31.2 points per game against the best defensive team in the league. He graduated from Davidson, 13 years after he left for the NBA following his junior season. He expanded his charitable reach: Since 2019, the Eat. Learn. Play. Foundation he and Ayesha founded has served more than 25 million meals to food-insecure children, spent $2.5 million on literacy-focused grants and distributed 500,000 books, according to Curry’s representatives. He has also provided seed funding for men’s and women’s golf teams at Howard University, a historically Black school, and started the Underrated Golf Tour, a junior circuit designed to make the game more inclusive. He is co-chair of Michelle Obama’s When We All Vote initiative. And now we name him Sports Illustrated’s Sportsperson of the Year. Curry, who also shared the award with the 2017–18 Warriors, joins LeBron James, Tom Brady and Tiger Woods as the only multiple-time winners. We salute him this year not just for what he did, but for how he did it.

Glory gaze: Curry called his fourth NBA championship his “greatest moment.”

Ezra Shaw/Getty Images

On a daily basis, Curry pulls off one of the toughest tricks in sports: He passionately seeks greatness without being consumed by it. He reminds us that stardom is not a license to be a jerk, and being a jerk is not a prerequisite for stardom. Longtime NBA fans can recite many stories about Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant belittling teammates to motivate them. There are no such stories about Curry. He can go weeks without giving anybody a pep talk, and, when he does, it’s usually pretty short: Come on! Lock in!

“Winning is fun,” Curry says. “We all know that. But to do it in a way that people speak on our culture, speak on my leadership, you have the respect of people around you—like, all that stuff matters in the big picture. And it’s hard to do.”

The only people Curry wears out are the ones defending him. Everyone else, he boosts. There are a lot of highly driven people in pro sports, and plenty of sweethearts, but who else besides Curry is both all the time? He says the losses in the 2016 and ’19 Finals sit with him more than the wins: “I still can put myself in those moments or feel that sense of emptiness. I feel that more now, looking back, versus the other ones for sure. That’s the age-old conversation, right? Like, I think Jordan has articulated that. Kobe as well. For me, they go hand in hand.” Still, his friends say his demeanor is the same after wins as after losses. Curry hears the criticism but says, “I don’t carry it home.”

Bob Myers, the Warriors’ general manager since 2012, says he has seen him down once—in the ’19–20 season, when Curry had hand surgery, Thompson had a torn ACL and the Warriors had no immediate hope.

Many people who know him call him the best person they know, and yet, because so much of Curry’s character is tied to not acting special, they are hesitant to make too much of a fuss about it. Jason Richards, who was two years ahead of Curry at Davidson, tells anybody who asks that Curry is a better person than a player, but casually refers to him as “the kid.”

Ayesha says, “I don’t know that I’ve ever seen him angry. He’s not argumentative. He never gets to that point. He’s always able to take a step back outside of himself and look at multiple sides. … As a human being, it’s a beautiful thing to watch, but as his wife, it’s kind of annoying.” She laughs. “It’s like, ‘O.K., Mr. Optimist!’ ”

“Winning is great,” says Myers, “but the man, the person … I really marvel at him.”

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Sportsperson of the Year Winners

This Curry self-assessment won’t go viral like his post-Finals comment, but it sums him up as well as anything: “I don’t need anybody to tell me I’m great or anything like that. I have a very high sense of self-confidence and what I can do. But there’s also the self-awareness, too: You’re not doing anything great in this world alone.”

He is so comfortable with himself that he doesn’t waste time on his ego. McKillop says, “If you text him or call him to say, ‘Great game, great this, great that,’ he won’t respond. If you say, ‘I hope you treat Ayesha like a queen today. Happy anniversary,’ he’ll get back to you.” Richards, who is Underrated’s director of athletic operations, says when his friends meet Curry for the first time, he gives them a warning: “Just so you know, he is going to make eye contact with you whenever you speak.” When Curry talks to his high school coach, Shonn Brown, he is more likely to ask about Brown’s team than mention his own. As a rookie, Curry walked down Bay Area streets quietly handing out $100 bills.