An ancient nematode awakens after thousands of nights of hibernation in a fossil squirrel den from the late Pleistocene.

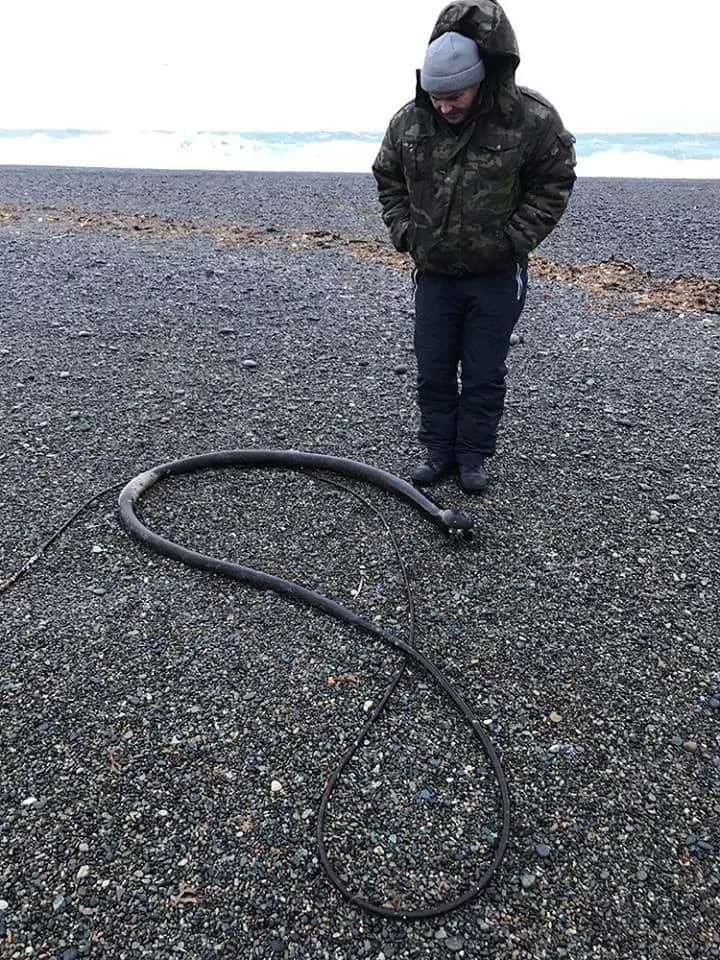

A small species of worm that remains after 46,000 years lies in the permafrost of Siberia, decades longer than previous resurrected worms. It belongs to the newly described species Panagrolaimus kolymaensis. The team discovered it curled up in fossilized squirrel burrows taken from permafrost soil near the Kolyma River in the northeastern arctic in 2002. Scientists revived frozen roundworms in 2018 but the date is unknown. and other of it.

Research published July 27 in the journal PLOS Genetics has found the answers to these questions. “Surviving in extreme environments for long periods of time is a feat only a few biological organizations can overcome,” said the team from Russia and Germany. “Here, we demonstrate that the soil-dwelling species Panagrolaimus kolymaensis has been dormant for 46,000 years under the permafrost of Siberia.”

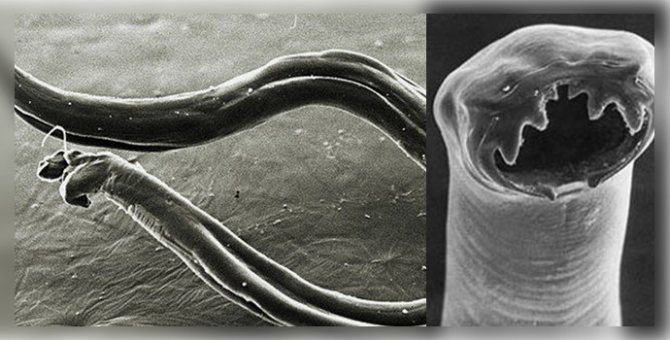

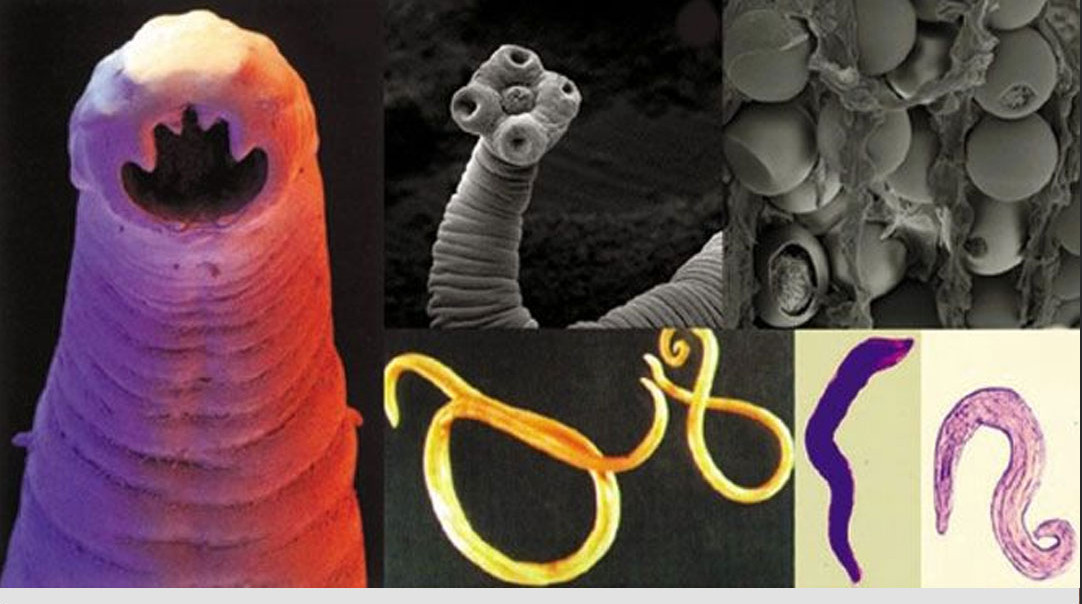

Organisms such as nematodes and water can enter a state of dormancy, a metabolic process called “cryptobiosis” (hibernation), in response to freezing or complete dehydration. In both cases, we reduce oxygen consumption and metabolic heat to undetectable levels.

Roundworms hibernate at the end of the Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), a period that includes the last glaciation. The permafrost has kept the organism unfrozen ever since. This is the longest hibernation period recorded in roundworms. Previously, the Antarctic nematode Plectus murrayi was frozen in agar and a specimen of Tylenchus polyhypnus was dried in the sample room for periods such as 25.5 and 39 years.

The researchers analyzed the genes of P. Kolymaensis and compared it with the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the first multicellular organism to have the entire genome sequenced automatically. C. elegans provides the perfect model for comparison. The results of the analysis revealed several common genes involved in hibernation.

To find out exactly how roundworms survive for so long, the team found a new group of P. kolymaensis and C. elegans and dried them in the lab. As the worms entered an anhydrous state, they observed a spike in a sugar called trehalose, which can help protect the roundworm’s cells from dehydration. They then froze the worms at -80 degrees Celsius and found that the drying improved survival for both species. Keeping frozen at this temperature without pre-dehydrating will die instantly.

Armed with a molecular mechanism to combat Arctic conditions, roundworms have evolved to live out in a state of hibernation throughout the year. Ancient nematodes can revive if they escape the permafrost. Substantial changes in the environment, including temperature variations and natural radioactivity, can awaken roundworms from a deep sleep state.