Want to win a million bucks? It’s easy. All you have to do is travel to Kiryat Yam, an Israeli coastal town near Haifa, and secure conclusive proof of the existence of a creature that has never, in thousands of years, been conclusively proven to exist.

Reports of the “Mermaid of Kiryat Yam” date back to 2009, which is when the town’s mayor set up the (tourist-attracting) award. According to eyewitnesses, the creature’s upper body resembles a human female child, the lower body a dolphin tail. She appears only at sunset [source: McGregor-Wood].

The mermaid has been swimming through human consciousness for millennia. She appears in early religious texts, including the book of Jewish law known as the Talmud, and in the mythologies of countless separate cultures [source: Stieber]. Rome’s Pliny the Elder described a mermaid-like creature in his first century reference work “Natural History” [source: Stieber]. She has since become a Disney princess, a Starbucks Coffee logo, a metaphor for transformation and dangerous desire and, most dramatically, an occasionally photographed flesh-and-blood animal.

In most incarnations, the mermaid has the head and torso of a woman, with long hair and, particularly in reports from sailors, large breasts. Her fingers may be especially long, possibly webbed [source: Stieber]. From the waist down, she has the scaly tail of a fish. Mermaids are typically beautiful, graceful and irresistibly alluring to human men — the latter a defining trait that leads to trouble.

Basically, they are Daryl Hannah’s character in “Splash.”

That’s the most popular vision of the fish-human hybrid. But the mermaid has been imagined by cultures around the globe for thousands of years. The ancient Syrian goddess Atargatis may have been the first, though she didn’t start out as a mermaid.

Mermaids, Conflicted Creatures

Stories of the beautiful Atargatis date back to 1000 B.C.E. in Syria [source: Bellincampi]. She is a protector goddess, associated with water and new life. In one of her common backstories, she falls in love with a human man. As usual, this works out poorly for the mortal: Atargatis accidently kills her lover. In shame and agony, she throws herself in a lake, set on becoming a fish. Her feminine beauty, though, is too powerful, and the transformation fails midway. She ends up with the tail of a fish but remains a woman above the waist [source: Sea-thos].

Like Atargatis, mermaids may be benevolent protectors. They may be vulnerable, like the deeply suffering protagonist in Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” who gives up her tail to walk on land with the man she loves only to be cast aside, turning to sea-foam in her heartbreak. Disney’s “Little Mermaid” Ariel, based on Andersen’s character, suffers but is ultimately rewarded for her goodness and bravery with a happily-ever-after. Ariel is a hero mermaid.

On the other end of the spectrum, mermaids may be flat-out evil. In German myth, mermaids called nixes use music to lure men into their river in order to drown them, similar to the sweet-voiced sirens depicted in Homer’s “Odyssey” [source: MarineBio Conservation Society]. (Sirens aren’t mermaids, though; different creatures entirely.)

But often, the picture is more complex. Duality, literally represented in the body of the mermaid, and transformation, a defining property of water, are central to the mermaid myth [source: Witcombe]. The West African goddess Mami Wata, Mother Water, is often depicted as a mermaid encircled by a snake. She is generous and nurturing, erotic and deeply jealous. In the hands of a loyal man, her magical comb and mirror impart instant wealth, but faced with betrayal, she rains down fury and destruction.

Mermaids are alluring and elusive, feminine and animal, protective and devastating. And imagined mermaids are almost always beautiful. It’s the most obvious key to their allure. But in real life, the mermaid picture isn’t always so pretty. One spotted near Indonesia in 1943 had the mouth of a carp.

Eyewitness Accounts of Mermaids

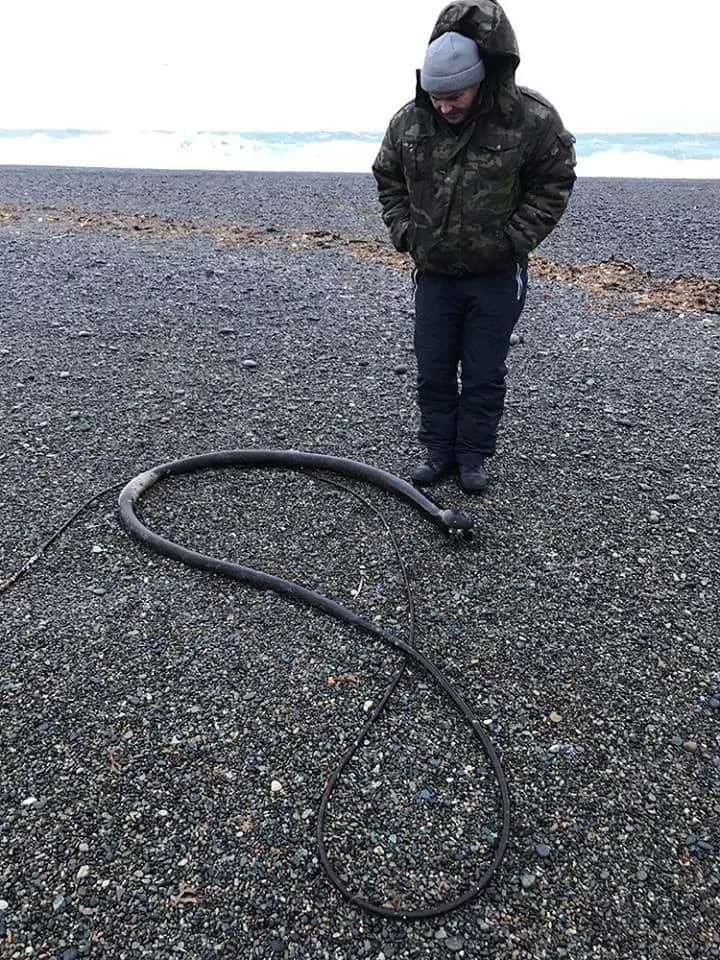

During World War II, Japanese soldiers stationed on Indonesia’s Kai Islands reported encountering a “monster” on the beach. It had a mostly human-looking body, but with webbed hands and feet, spines running down its head and neck, and a mouth that looked like a carp’s [source: Cryptomundo]. The villagers knew of these creatures, as they sometimes got trapped in fishing nets [source: Cameron].

Coastal dwellers and sailors are the most common reporters of mermaid sightings. Explorers like Christopher Columbus, John Smith and Henry Hudson all have reported seeing mermaids. Hudson saw one with long, black hair, fair skin, large breasts and a porpoise tail in 1608, near Russia [sources: Cavendish, The New York Times]. John Smith, after Pocahontas saved him, was in the West Indies in 1614 when he almost fell in love with a mermaid with long, green hair; he thought she was a woman swimming until he glimpsed below the waist. Columbus spotted three mermaids in 1493 but said they were not as pretty as he expected them to be [source: Stieber].

They’ve been seen in waters around Canada, England, Scotland, West Africa, America, the Netherlands and Israel [source: Stieber]. A videotaped “encounter” off the coast of Greenland became big news in 2013 when Discovery’s Animal Planet promoted it, albeit in a fake documentary called “Mermaids: The New Evidence” that saw massive ratings and followed on the heels of its 2012 (also fake) show “Mermaids: The Body Found.”

Here’s how the 2013 program presented it: In 2010, marine biologist Torsten Schmidt (not an actual scientist) was with his team in the Greenland Sea, performing seismic mapping 3,000 feet (1 kilometer) below the surface, when they encountered sounds they’d never heard before. Perplexed, they recorded them and asked their employer, the Iceland GeoSurvey, if they could investigate further. The Iceland GeoSurvey rejected the request.

So Schmidt took a team down on his own, and they “found” something. In March 2013, they captured video of an encounter with a human-like creature with webbed hands. The rest is ratings history.

Not surprisingly, seafarers’ mermaid encounters are often rejected — dismissed as hallucination, the result of too many days at sea or an overactive imagination [source: MarineBio Conservation Society]. Scholars have claimed that Christopher Columbus mistook manatees for mermaids (which might explain his disappointment about their looks). One officer who returned from the Kai Islands after the war asked Japanese biologists to investigate the monsters he saw, but they declined [source: Cameron].

And understandably so. The mermaid thing is a tough sell. That doesn’t mean mainstream scientists don’t talk about it, though.

Mermaid Science

An article about mermaids appeared in the scientific journal Limnology and Oceanography in 1990. In it, respected biological oceanographer Karl Banse offered a tongue-in-cheek analysis of mermaid biology and lifestyle. Banse took known facts about aquatic life and extrapolated to theorize about mermaid characteristics [source: McClain].

In “Mermaids: Their Biology, Culture, and Demise,” Banse suggests that there were once three species of mermaid, distinguished by their geographical locations. All would have been warm-water creatures, as they lacked the heavy blubber necessary to live in colder seas. The ones Columbus saw were the species Siren indica, who lived in the Atlantic Ocean.

Mermaids, says Banse, fed on the flesh of humans. It’s worth noting, though, that a 1967 sighting off the coast of British Columbia had a mermaid eating salmon [source: Cameron]. In terms of physical build, Banse disagrees with the traditional depiction of the mermaid’s tail as covered in smooth scales. Rather, he theorizes, mermaid tails had “horny skinfolds” similar to those of armadillos and anteaters.

Due to the presence of only two breasts, he surmised they gave birth to one or two young at a time. The paper leaves out the details of reproduction, though the lack of human genitalia seems to point to fish-like fertilization. We might look to Hindu myth for clues to the birthing process: The god Hanuman once had a child with Sovann Macha, the Golden Mermaid, and the child was expelled from the mermaid’s throat.

So what happened to all these mermaids? Extinction, says Banse — mermaids were wiped out by a ballooning jellyfish population after humans overfished other marine life, destroying the ecological balance. Mermaids’ thin skin offered no protection from jellyfish stings.

But clearly they’re not extinct — at least judging by the multiple sightings in Kiryat Yam. Or the testimony of (fake scientist) Torsten Schmidt in “Mermaids: The New Evidence.” Or the footage presented in Discovery’s previous production, the hugely successful “Mermaids: The Body Found,” which painted such a “wildly convincing picture” that the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) decided to step in.

After fielding countless calls in the wake of the airing of “The Body Found,” the NOAA released a statement, trying to clear up the issue this way: “No evidence of aquatic humanoids has ever been found. Why, then, do they occupy the collective unconscious of nearly all seafaring peoples? That’s a question best left to historians, philosophers, and anthropologists” [source: Jspace].

Possibly. In the meantime, the $1 million reward for proof of the Mermaid of Kiryat Yam is still up for grabs.

Lots More Information

Author’s Note: How Mermaids Work

If you’ve ever tried to research a mythological creature, you know it’s tough to come by much consensus. Every god has five backstories, every sighting 10 accounts, every explanation at least 12 interpretations. I tried to include here the information that seemed most agreed-upon or widely reported, but in many cases I had to settle for what was simply the most compelling. So just enjoy. Mermaids are good stuff.