The sea is primordial, vast and ever-changing, the source and destination of all waters. It advances and retreats with the tides. It gave rise to all life, yet its winds and waves bring death to the unwary or the unlucky. Given these connotations, it’s small wonder that the sea plays such an essential role in so many cultures’ creation myths, or that its gods and monsters rank among the most potent. To control the seas is to master chaos and to wield the power of creation and destruction [sources: Barré; Chevalier and Gheerbrant].

These oceanic associations spill over into the forms taken by sea gods, their servants and assorted briny beasts. The Mesopotamians saw their goddess Tiamat as a sea monster or many-headed dragon, an image that evokes the undulating power of waves, the force of floods or the destructive fury of tsunamis. Other deities, like the Greek sea god Poseidon, used monsters of the deep to visit their wrath upon mortal fleets and coastal cities. Still others demonstrated their might by destroying monstrous sea creatures, as God brought low Leviathan in the Old Testament.

Some psychoanalysts consider sea monsters, particularly the ones we imagine dwelling in the deepest ocean, as symbolizing the unconscious mind, which follows its own sinuous paths even while the surface mind seems placid. We mirror the capriciousness of nature in our own protean natures, and we project our fears of both onto the outside world [source: Haven].

Another reason for our belief in sea monsters is summed up by Jules Verne in his 1870 novel “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea”: “Either we do know all the varieties of beings which people our planet, or we do not. If we do not know them all — if Nature has still secrets in the deeps for us, nothing is more conformable to reason than to admit the existence of fishes, or cetaceans of other kinds, or even of new species …”

The unknown invites us to populate it with creatures of our own invention, and vice versa: If we believe in undiscovered or unconfirmed creatures, we naturally imagine they live in inaccessible climes, be they high in the Himalayas, deep within an unexplored jungle — or far below the all-concealing waves.

Whatever the reasons, most seafaring cultures have sea monster myths or folktales. They are preserved in manuscripts, in the margins of old maps, on the walls of Hindu temples and in the rock carvings of American Indians [source: Morell].

But is there a drop of truth to any of these tall tales? And how might we find out?

An Undersea Bestiary

One clue can be found in the many forms sea monsters take. According to myth and legend, such creatures range from the gigantic to the human-sized, from the fanciful to the almost familiar.

In the latter category we come across the Scandinavian sea monster called the kraken, the subject of tales dating back to 1180 and the inspiration for a poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (see sidebar). The creature, perhaps inspired by actual sightings of giant squids, reputedly dwelled in the waters off Norway and Iceland. Legend says it measured more than 1.5 miles (2.5 kilometers) across and sported arms the size of ship’s masts. Indeed, the beast was reputedly so vast that sailors could mistake its body for land or its tentacles for a ring of islands. As a result, the greatest danger it posed was the whirlpool it created while surfacing or submerging [source: AMNH].

Other familiar creatures that assumed monstrous proportions in legend included giant sea serpents and gargantuan turtles [source: Haven].

Far more than mere curiosities or threats, sea monsters often played a vital symbolic or religious role in cultures around the world, some of which viewed them in a more neutral or positive light. In Hinduism, the makara — a half-animal, half-fish — transported Ganga, the goddess of the river Ganges, and Varuna, the god-sovereign of Vedic Hinduism, who is also linked with oceans and waters. The Chinese viewed most dragons as benevolent and associated them with good luck and procreative power [source: Morell]. On the other hand, in Native American stories, the giant water creatures called unktehila represent the world’s evils and must be defeated by the Wakinyan, or Thunder Beings.

On a smaller scale, sea monsters could assume the form of dangerous, often enthralling, mer-humans or animals. For example, Scandinavians and Scots alike spoke of horse-like, shape-shifting kelpies that lured children to watery graves.

Myths and religions also named specific sea monsters. We’ve already discussed Tiamat, the many-headed dragon goddess of the primordial sea, and the Old Testament creature Leviathan, who scholars believe was influenced by her [sources: Barré; Encyclopaedia Britannica]. The Greeks gave us another such monster, named Cetus by the Romans and enshrined as a constellation. Poseidon sent Cetus to destroy the kingdom of King Cepheus as punishment after Cassiopeia, his wife, boasted that her daughter was more beautiful than the sea nymphs. The creature — which is named after the Latin word for whale but is usually depicted as having paws, a doglike head and a curling fish tail — rampaged through the kingdom until the royal couple offered the daughter, Andromeda, as a sacrifice. Perseus famously slew the creature and saved her.

Such tales form an essential component of cultures the world over. They enrich our languages with symbol, metaphor and, in some cases, belief. But why do we fall for them hook, line and sinker?

Why We Believe in Sea Monsters

Our belief in sea monsters flows from many sources, but stories about them draw at least some of their power from the strange interactions between the human mind, extreme environs and unusual experiences. Put another way, sea monsters occupy the ever-shifting sands where the human subconscious and the physical world meet.

For example, Scylla and Charybdis — dangerous creatures made famous in Homer’s “Odyssey” — might have been based on real seafaring dangers that sailors faced in the Straits of Messina. Scylla, described as having 12 feet, six heads atop long, sinuous necks, and mouths bristling with rows of sharklike teeth, was said to reach out from her cave to grab and devour any who ventured too close. Charybdis lay on the opposite shore and periodically swallowed and regurgitated the waters there. Some scholars think Scylla represented a dangerous rock or reef, while Charybdis personified a whirlpool [source: Encyclopaedia Britannica].

The unktehila of the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, Kiowa and other tribes arose in part from dinosaur bones found by tribal hunters. People in China once venerated the remains of lucky “Guizhou dragons,” which turned out to be the bones of 12- to 14-inch-long (30- to 36-centimeter) marine reptiles called Keichousaurus hui [source: Morell].

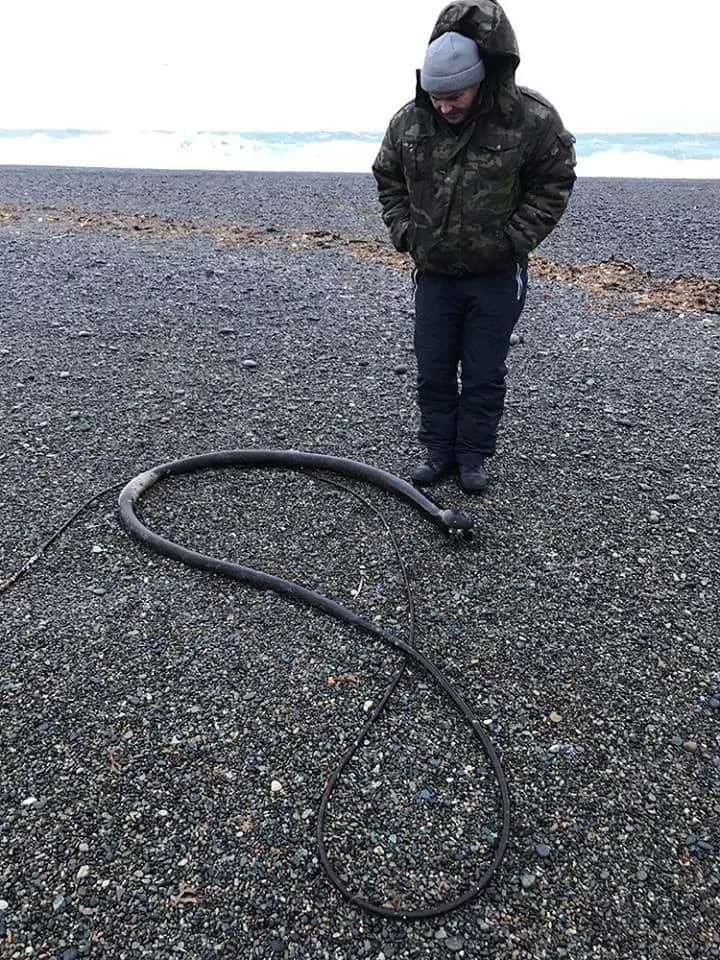

Similarly, other fabled sea monsters may simply be fish stories — misremembered or embellished tales of real encounters, either with living creatures at sea or badly deformed and bloated corpses washed up on shore. Sailors might have seen sea serpents in porpoises swimming in a rippling line, in large masses of seaweed or in 30- to 46-foot (9- to 14-meter) basking shark. And then there’s the oarfish, a long, eel-like fish with a red, bristly head crest and long, spiny dorsal fin. These serpentine monsters, which can approach 36-50 feet (11-15 meters) long, swim in an undulating motion that could create apparent “humps” on the sea’s surface.

Kraken might well have been based on giant squids, which can reach lengths of 50-70 feet (15-20 meters). A famous legend tells of a sea serpent battling a whale, its mighty arms coiling around the hapless cetacean and dragging it beneath the waves [source: Encyclopaedia Britannica]. This comports with nature, where giant squids are known to tussle with sperm whales, leaving behind sucker and claw scars, or even the odd tentacle for whalers to recovered later from the cetacean’s stomach [source: AMNH].

The open ocean is a terrifying, humbling place, and ancient sailors faced a tenuous existence; it was natural to imagine what threats or treasures might dwell, unseen, beneath the surface. Such fancies might have been aided by transitory hallucinations, brought on by misfiring neurons caused by head injury, physical illness, drugs, stress, sleep deprivation, fatigue or mirages [source: Ocean Navigator].

But does that mean that there’s no room in the scientific imagination for real sea monsters?

The Scientist and the Sea Serpent

On the 6th of July 1734, when off the south coast of Greenland, a sea-monster appeared to us, whose head, when raised, was on level with our main-top. Its snout was long and sharp, and it blew water almost like a whale; it has large broad paws; its body was covered with scales; its skin was rough and uneven; in other respects it was as a serpent; and when it dived, its tail, which was raised in the air, appeared to be a whole ship’s length from its body.

— Hans Egede, Norwegian missionary, later bishop of Greenland [source: AMNH]

In 1817 and 1819, more than 200 residents of Glouster Harbor, Massachusetts, recounted seeing a giant creature that resembled a serpent. “The Great Sea Serpent,” an 1892 book by professor A. C. Oudemans, describes more than 200 reports of unknown sea creatures. But then thousands of people over the years have reported sighting the Loch Ness Monster, aka Nessie, yet no scientific evidence for its existence has yet been found — and not for lack of trying.

What are scientists to make of such creatures? On the one hand, we still discover strange new sea fauna over time, and by some estimates as much as 95 percent of the ocean’s lowest depths remain unexplored. We know, too, that some creatures that resemble sea monsters, such a giant squid and oarfish, spend most of their lives in deep or deep-ish waters, entering the shallows or washing ashore only when sick or dying. So it seems reasonable that remarkable creatures could yet exist, whether encountered by sailors or completely undiscovered.

But admitting the possibility that we have not seen all that nature has up her watery sleeve is not the same as conceding the existence of creatures that defy the laws of physics, chemistry and biology. Scientists may not be able to comment on the fanciful, and might find it difficult to disprove the existence of a thing, but they certainly can apply known principles to establish boundaries on what might lurk undiscovered beneath the waves. After all, the first coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) was discovered as recently as 1938, and the Megamouth shark, caught in 1976, was even more recent, but both conformed to the basics of oceanographic physiology [sources: Smithsonian; Western Australian Museum].

Such answers are the best we can expect for now, until we drain the seas or until some rough beast emerges from them to announce its presence in no uncertain terms.

Frequently Answered Questions

What crossword monster is opposite Charybdis?

Lots More Information

Author’s Note: How Sea Monsters Work

It’s worth noting that descriptions of legendary creatures change as our views about real creatures evolve. The Loch Ness Monster, which Scots probably once imagined as a sea serpent or kelpie, took on a much more plesiosaur-like form after scientists began studying and publicizing dinosaur discoveries.

Moreover, it can hardly be coincidental that, the more we know about the ocean and its inhabitants, the less common sea monster sightings become. Still, I’m pulling for the sea monsters — or anything else that can remind us that mysteries still exist.