The incident happened in the Santa Rosa area in the Guanacaste reserve, Costa Rica. The team from the University of Louisa were firsthand witnesses of the attack from start to finish.

According to Dr. Katharine M. Jack, while observing a herd of white-faced monkeys, he noticed that one of the young in the group was busy playing and became the target of a 2 m long predatory python.

The animal was tightly coiled by the python and then began to squeeze. Realizing the dangerous situation, the leader of the pack alerted the whole group. Then, they rush to attack the opponent, despite the possible danger.

The team said that, although they do not have a close relationship with the captured monkeys, they still join forces to fight to save their fellow monkeys.

Finally, the python was forced to release the baby monkey and the monkeys escaped successfully. Not getting any bait, the python also suffered the attack marks on it.

Guanacaste Reserve is a World Heritage Site in the northwestern region of Costa Rica. This place covers an area of up to 1,470 square kilometers, which includes national parks, reserves, and wildlife refuges.

In 1994, this area officially became part of the national park system and then a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999 thanks to its diverse topography, tropical dry forests and important wildlife. important.

Anthropologists from Tulane University have captured incredible footage of capuchin monkeys teaming up to rescue one of their own from the strangling clutches of a Boa constrictor. The video, along with the scientists’ description of the incident, were recently published in the journal Scientific Reports.

In the summer of 2019, Professor of Anthropology Dr. Katharine M. Jack and her colleagues were following a group of 25 white-faced capuchin monkeys in Sector Santa Rosa of the A?rea de conservacio?n in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. A few of the juveniles were enjoying a light-hearted play session when the attack occurred. The terrifying ordeal abruptly begins roughly 28 seconds into the video below and lasts just 19 seconds.

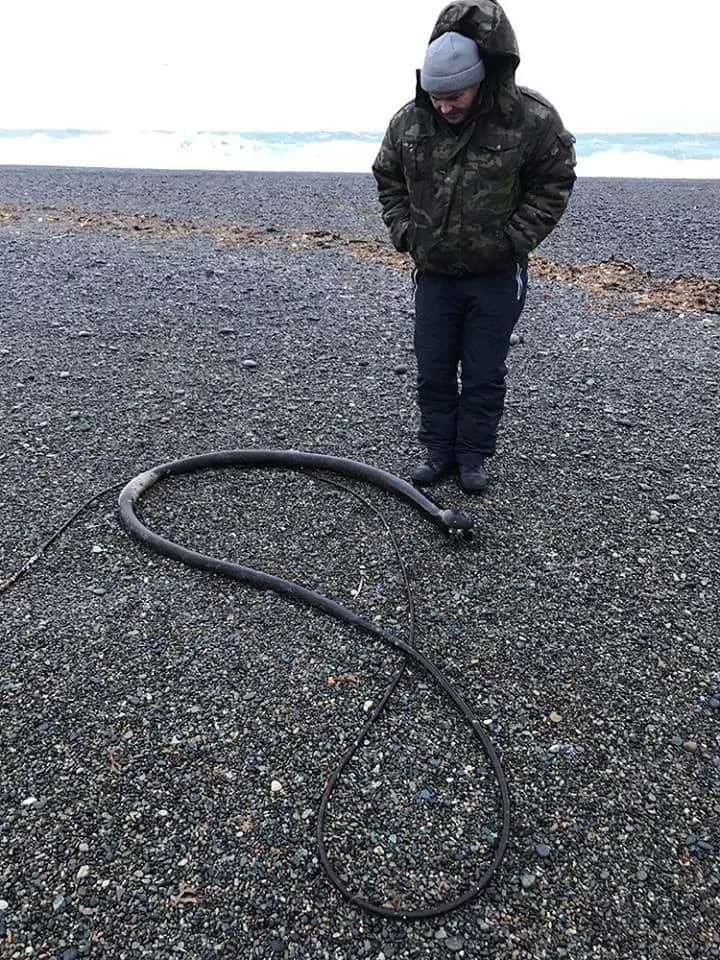

Around 28 seconds in, you can hear the victim, a 6-year-old juvenile, start to scream as the two meter-long Boa constrictor begins its suffocating embrace. A second later, a subordinate adult male sounds the snake alarm call to rouse the rest of the group. Just four seconds afterwards, the group’s alpha male charges toward the snake and starts to furiously bite and scratch it, drawing blood. Soon afterward, two older females join the alpha male in attacking the Boa while also attempting to pry the juvenile from its clutches. They succeed after a few seconds, ending the attack and scurrying away at about the 47-second mark.

While predation events like these occur frequently, they are rarely observed by scientists. According to the researchers, the swift, heroic actions of the capuchin group “clearly support the hypothesis that predation has been a strong selective force driving sociality in primates.” A tight social bond can be the difference between life and death for an individual within a group. And direct kinship is not required. In this case, the group’s alpha male risked his life to save the juvenile even though he was not actually related to the young monkey.

This event in particular drives home the much-discussed notion that snakes and primates co-evolved, shaping each other’s behavior and physiology as predator and prey.

“The threat of constricting snakes may have been a particularly strong selective force in early primate evolution when primates were small bodied and, therefore, more susceptible to fall prey to constricting snakes,” the researchers conclude.