One of the most notable Thoroughbred racehorses in history was Seabiscuit. Americans flocked to racetracks in droves between 1936 and 1940 to see the little, awkward racehorse succeed. He walked awkwardly yet ran with unmatched speed; he was polite but ferociously competitive; and he resisted until he yielded. His poor early racing results led to his later success on the turf.

Seabiscuit appeared to have nothing in common with his regal ancestors, despite the stallion’s connection to the famed Man o’ War through his gorgeous offspring Hard Tack. His tail was stunted, his legs were short, and his body was thick. When he ran, his left foreleg stabbed out erratically; some referred to the movement as a “eggbeater gait.”

Even worse, when he was a young horse, he had not shown much aptitude for running quickly. James Fitzsimmons, Seabiscuit’s initial trainer, claimed that the horse was “dead lethargic.” In hindsight, it seems the horse’s bad performance and attitude were more a result of how he was treated than a result of his skill or moral fiber. The horse had competed in 43 races by the time it was three years old, which is more than many Thoroughbreds do in their whole careers. Riders beat him heavily until he reached the speed they believed he was capable of.

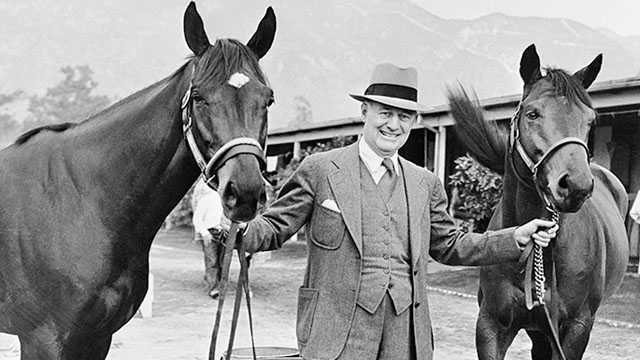

When Seabiscuit was taken into the care of owner Charles and trainer Tom Smith in the middle of his third season, he was refusing to eat and weighed 200 pounds less than he should have. In his stall, he paced agitatedly and lashed at everyone who approached. Before being purchased by Howard, the horse was ridden by a jockey who described him as “mean, restless, and tattered.”

Smith gave Seabiscuit a high-quality Timothy hay to eat and allowed him to sleep as late as he liked to start his rehabilitation. Since horses enjoy company, the trainer built a spacious stall for the new boarder and brought in Pumpkin, an old, placid horse who would eventually become Seabiscuit’s lifelong friend. Pocatell the stray dog and Jo-Jo the resident spider monkey both developed affection for the stall and moved in. Seabiscuit unwinded in the presence of this peculiar zoo, and the training’s actual work began.

The Biscuit startled everyone when Smith brought him back to the track with his new jockey, Red Pollard, on board. Seabiscuit triumphed against opponents at various distances and tracks. His status as a viable candidate for the famed Santa Anita Handicap in southern Los Angeles, with its $100,000 winner-take-all purse, quickly gained the attention of horse enthusiasts. Seabiscuit put on a strong performance in the Handicap in February 1937, but he lost by a nose because Pollard faltered in the closing stages. But the horse’s second-place finish propelled him into the national stage.

Howard prepared his horse for a lengthy cross-country racing season in March. He told the media, “Seabiscuit will take on all comers, and he’ll mow them down like grass.” Howard was correct; Seabiscuit wiped out the competition along the whole Eastern seaboard that spring and summer. By August, it appeared like War Admiral, the 1937 Triple Crown victor, was the last horse still standing against Seabiscuit’s assault. The stallion was Man o’War’s son and was widely regarded as the lone heir to his sire’s incredible speed.

On November 1, 1938, at Maryland’s Pimlico Racecourse, the two horses finally faced off in their eagerly anticipated one-on-one contest. One in three Americans, or 40 million individuals, throughout the nation turned on their radios to listen. Many Americans secretly supported Seabiscuit as the underdog. But War Admiral was the favorite among most bettors.

Nearly everyone anticipated War Admiral to sprint to the front, but Seabiscuit, who had been prepared to take off at full speed, instead took the lead and set the pace. He led for the majority of the race, but in an unusual maneuver, Seabiscuit’s jockey that day, George Woolf, slowed him down on the backstretch before the last bend, allowing War Admiral to catch up. Red Pollard, who was out due to an injury the night before the race, had told Woolf that once a horse gives Seabiscuit the old look-in-the-eye, “he begins to run to parts unknown.” The horse indeed behaved in that manner. In the stretch, he drew ahead of War Admiral and won the century’s greatest horse race by four lengths.

When Seabiscuit stumbled and tore his suspensory ligament six weeks later, people believed that would be the horse’s lifetime accomplishment. Although no one anticipated him to race once more, Howard insisted against using the word “retirement.” Instead, he returned to California with the horse to give it a “good, long rest.” Together, Pollard and the horse recovered there while taking protracted walks around Howard’s huge property and making a little more progress every day. The jockey subsequently recalled, “Seabiscuit and I were a pair of old cripples together, all washed up. But we both regained sound outside among the owls’ hooting.

The handlers of Seabiscuit made an almost unbelievable revelation toward the end of the 1939–1940 racing season: Seabiscuit would run once more in the Santa Anita Handicap scheduled for March 1940. He would attempt the hundred-grander for the third time. He had previously fallen short to Rosemont by a hair. The second time, he was severely bumped at the beginning, and after mounting one of the most incredible comebacks in racing history, he lost at the finish line once more. The horse would be seven years old this time, which is old by racing standards. He would be ridden by Pollard, whose damaged leg was still weak.

In preparation for a sprint, Seabiscuit pulled at Pollard’s hands as the race came to a close. Seabiscuit was surrounded by two horses—one on the rail in front of him and the other on his outside—and had nowhere to go. A jockey riding another mount overheard a prayer from the group at that very moment. It was Pollard’s idea, who thought that the angels would part their way so that his Seabiscuit could pass. A void appeared. “Now, Pop,” Pollard yelled. Seabiscuit picked up speed to take the lead despite the horses’ frenzied pace. Kayak, a closer, caught Seabiscuit in the stretch. Seabiscuit turned to face a rival for the final time in his racing career before sprinting away from the opposition. For the distance, it was the second-fastest time ever set on an American track. Don’t assume that he was unaware that he was the hero, Pollard advised subsequently.